Making space for a handmade web

There’s a resurgence of small, handcrafted sites challenging the current trajectory of the internet. Joining the movement is as simple as making your own.

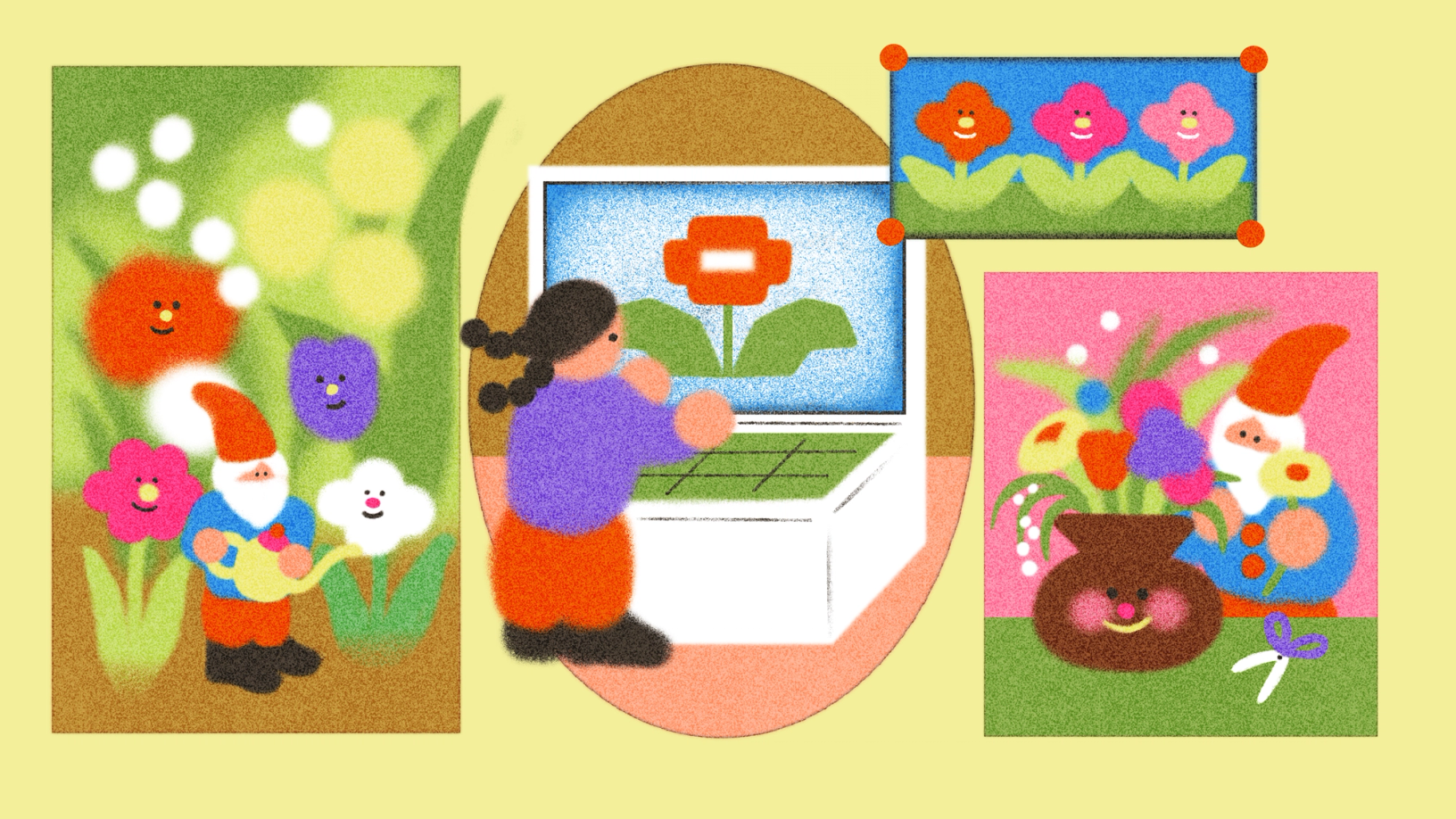

Hero illustration by Zoey Kim

I make art using the internet as a medium. From unearthing YouTube comments left under love songs to turning my desktop into a landscape full of browser windows, I work to reimagine what the internet can be. When I share websites I’ve made, people often respond with comments like “I wish the web were like this.” These reactions confuse me: I just made this website, and the web still is very much like this: personal, poetic, expressive. That is, if you know where to look.

Before the web was more commercialized, it was personal. In 1994, the web hosting service GeoCities allowed anyone to own a 2 MB parcel of digital land. Handmade and amateur webpages were abundant and unpolished, organized into thematic “neighborhoods” like Napa Valley for wine lovers and foodies, or Silicon Valley for technophiles. At its peak, GeoCities hosted 38 million web pages. A website was a way to represent yourself and connect to others, a space to tend and call your very own.

Today, there are more websites than ever before, but the internet somehow feels more constrained. While new tools have democratized the web, they’ve also flattened it. The imperfect, handmade character of websites has been sanded away in favor of efficiency, and social media platforms have risen in the stead of amateur sites. Many of us conform to these containers and retreat from expressing our authentic selves publicly—what writer and entrepreneur Yancey Strickler calls the ‘dark forest’ of the internet, where genuine expression gives way to self-censorship and fear of judgment.

Yet in certain pockets, a more personal internet persists. Neocities, founded in 2013 to archive GeoCities websites, now offers free hosting services, continuing the legacy of the defunct platform. In the past two years, it’s grown to host nearly a million sites. Institutions like Rhizome, the Center for Net Art, and the School for Poetic Computation hold exhibitions and workshops supporting internet art. Efforts like DWeb, largely supported by the Internet Archive, help actualize a more decentralized and distributed model of the internet—one that might truly be owned and shaped by all of us.

If the idea of a more handcrafted internet resonates with you, the best way to be part of the movement is simply to make your own website. This may seem intimidating if we expect webpages to be a holistic reflection of ourselves, like a resume, portfolio, or blog. We limit the web as a medium when we expect that a website must fulfill a host of needs, or serve any function at all. A website doesn’t need to be anything but your own. Even the fairly innocuous idea of a homepage puts undue pressure on a website to be comprehensive and unchanging: a website doesn’t have to be a “home” for anyone. Alternatively, think of a website as a space that changes and grows—not a fixed destination, but one part of a shared environment. In response to uniformity and standardization, we can leverage our skills and tools to build online spaces that feel truly personal.

What if we didn’t think of a website as one thing that answers to a million people? What if instead, there were millions of websites, each one handmade by a single person?

The range of possibilities is vast: You can tend a website for decades, or just a few days. It can be laser-focused on a single topic, or present a vibrant mix. It can lean technical with diagrams and code, or poetic with artistic expression. It can address an entire community, or a single loved one. What if we didn’t think of a website as one thing that answers to a million people? What if instead, there were millions of websites, each one handmade by a single person? In addition to the examples above, I offer these prompts to inspire a different kind of web:

- A website that isn’t always awake: Online spaces might benefit from temporal constraints, just like their real-world counterparts. For example, the website for the camera store B&H closes for religious observances, as their brick-and-mortar locations do. A series of websites I made, Cloudwatching and Stargazing, are only accessible during the day and night, respectively. Websites can also have set expiration dates. Experiments like the Internet Stoop lived online for a brief 12 hours, and Reddit’s The Button meta-game ended in five days, once the button was left unpressed for 60 seconds. After all, nothing online lasts forever—domain names need to be renewed, and people have limited resources for maintenance.

- A website that’s hard to find: Websites that take work to discover are their own kind of reward. Take the browser-based video game Black Room by Cassie McQuater, hosted on an intentionally illegible URL, or the YouTube aggregator Default Filename TV, which surfaces home videos uploaded directly from cameras without renaming any files. If social platforms and search engines favor algorithmic optimization and distinct branding, obscurity can be its own distribution tactic. These gems are only discovered by surfing the web, going from link to link; they wait for the right person to stumble upon them.

- A website without ownership: Akin to the idea of abandonware, or software now ignored by its manufacturer, websites can be divorced from their authors and used as fictional tools. Mysterious links depict alternate realities, or invite the visitor to project their own ideas. The internet art duo JODI’s website, launched in 1995, contains a mesmerizing labyrinth of ASCII landscapes that you can wander for hours. Thousands of contributors help author the SCP Foundation, which postures as a wiki for a fictional organization securing paranormal threats. Similarly, the game Neurocracy tasks the user to solve a murder in a fictional Wikipedia set in the year 2049.

A more personal web becomes possible once we turn away from our preconceived notions of what a website must be. Let’s use our tools to continuously push at the boundaries of the web. Doing so will create a more creative, expansive environment that allows us to reclaim our agency and reinvigorate our collective understanding of software as an artisanal craft. Instead of concentrating on a few, monolithic sites, what if we visited many, more personalized sites? We should explore the far reaches of the web and invite our friends to join in: After all, we make the internet, and only we can build the web we want.

We turned six big ideas percolating around the Figma office—written from the perspective of devs, designers, analysts, writers, PMs, card-carrying generalists—and put them on record. Here’s a look at what’s on our minds for 2025.

Further reading

- “I am a poem I am not software” by Robin Rendle (2023)

- “My website is a shifting house next to a river of knowledge. What could yours be?” by Laurel Schwulst (2018)

- “Spirit Surfing” by Kevin Bewersdorf (2008)

- “A Handmade Web” by J. R. Carpenter (2016)

- “A Vernacular Web: The Indigenous and the Barbarians” by Olia Lialina (2005)

- "Reenvisioning the Internet: Create Tools that Reveal its Ideological Infrastructures” by Gary Zhexi Zhang (2019)

- “Queer Servers and Feral Webs” by Austin Wade Smith (2023)

- “Why Do We Call it a Homepage?” by Jay (2020)