Meet the nonprofit training formerly incarcerated people for careers in UX design

Oakland, California-based CROP Organization wants to forge a better path for those facing the challenges of reentry. We caught up with the founders and first-ever cohort of fellows to learn about their mission to create new inroads to the world of tech.

“You can learn lessons at rock bottom that you’ll never find at the mountaintop,” says Jason Bryant, Director of Programs at the new nonprofit Creating Restorative Opportunities and Programs (CROP), which helps formerly incarcerated individuals who are dedicated to rehabilitation and skill-building ease back into society and the workforce. CROP harnesses their potential by equipping them with UX design skills using Figma.

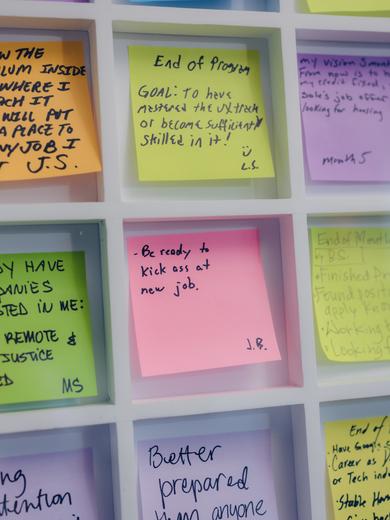

The result is its year-long Ready 4 Life program, which aims to lower California’s 50% recidivism rate through four pillars: personal development, career training, employment services, and stable housing. In addition to their own apartments on CROP’s residential and training campus in West Oakland, the 12 fellows benefit from personal coaches and a monthly stipend—all part of the program’s mission to show the public that given the right opportunity, tools, and resources, someone can beat the odds and transform their life.

Photography by Damien Maloney.

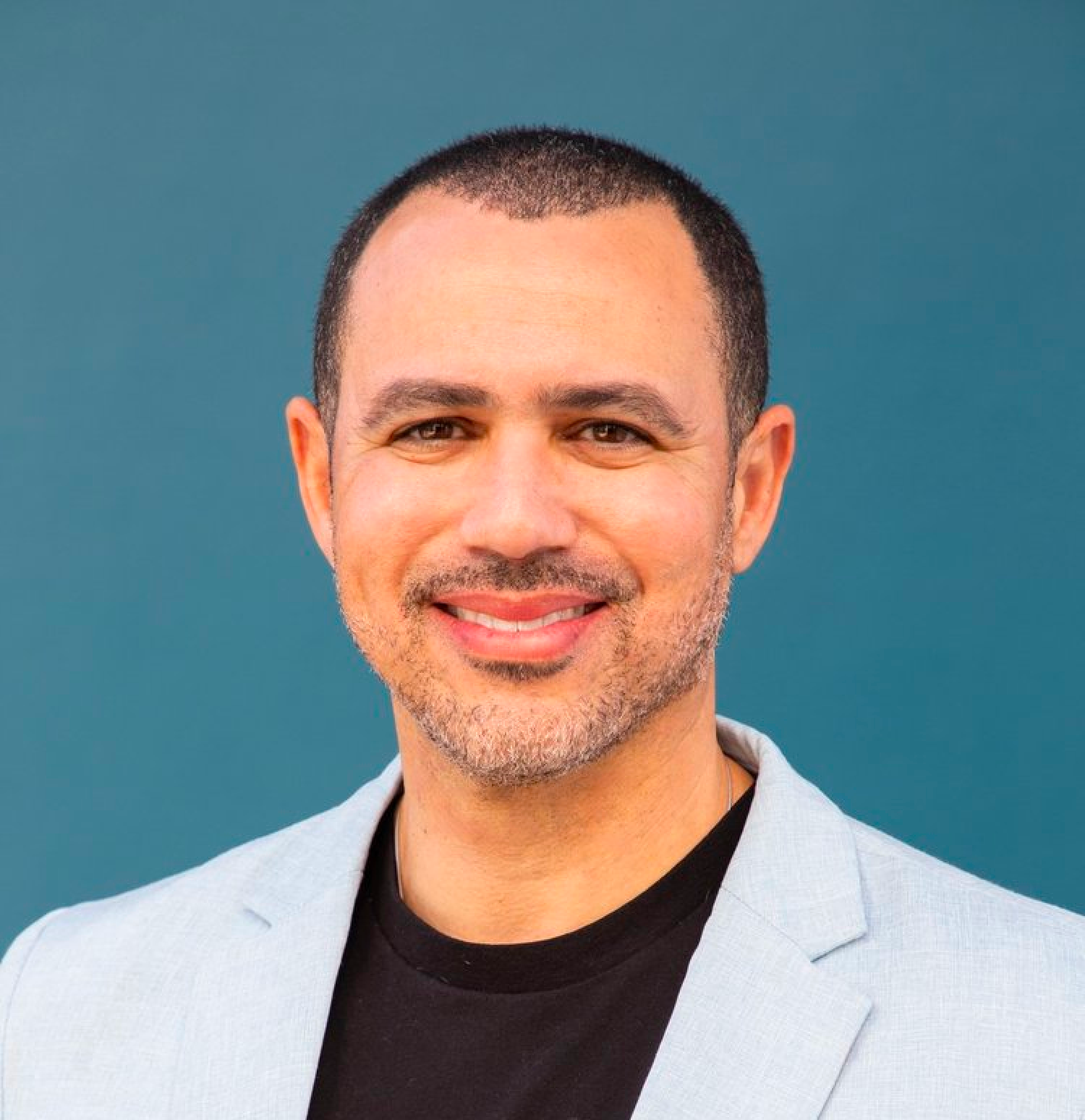

With classes in full swing, we caught up with Director of Programs Jason Bryant, UX Track Instructor Alexis Bustos, and UX design fellows Michele and Ron Scott (no relation) to talk about what it takes to overcome social stigma, build new lives, and envision new futures.

Jason, CROP was born out of the co-founders’ experiences in prison. Can you share a bit about that?

Hear more of Jason’s story in this episode of The Prison Post, a podcast started by Richard Mireles, Director of Outreach and Engagement at CROP.

There were four of us—myself, Ted Gray, Richard Mireles, and Matthew Braden—who had been working together for over a decade inside building programs under the name of CROP. A good friend of ours, Ken Oliver, had paroled about a year before and identified some serious service gaps in reentry: fractured programs with siloed employment, housing, and counseling services. So we sat around a table, 100 years of incarceration between the five of us, and reimagined reentry. What would a program look like that provided people with holistic, wraparound support and every opportunity to succeed? That's how we developed CROP’s Ready 4 Life program.

Each year, California taxpayers spend approximately $106,000 per person in prison, and 3.4% goes toward rehabilitation. The CROP program costs roughly half that per person.

In January of 2021, Ted and I had the good fortune of speaking with California Governor Gavin Newsom to thank him for his grace and our freedom, and share our plans. He loved the idea. We went to work with the legislature, and the governor signed a partnership with us for three years to the tune of $28.5 million. Since then, we’ve been building, scaling, creating new partnerships, and working our fingers to the bone.

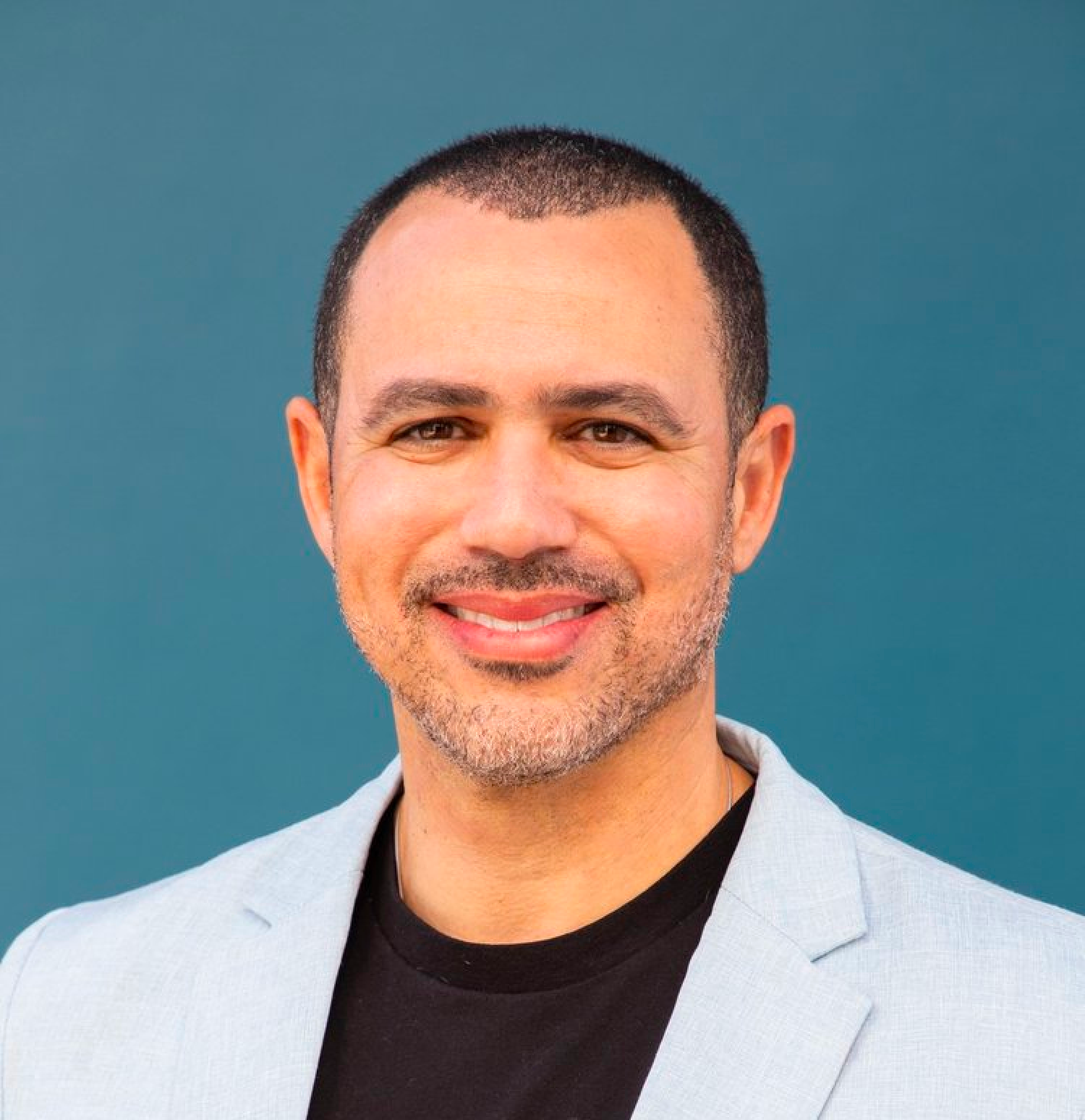

Alexis, you were a UX designer for five years before joining CROP. What drew you to this mission?

I was longing to make a tangible impact on diversity and inclusion in tech. When I met the CROP team and saw their passion, I knew I had found an opportunity to walk the walk. It only took me 1.2 seconds to connect with the fellows and understand how their problem-solving abilities, their storytelling, and their way of connecting to people are going to be so influential in the tech space. They’re primed and ready, and all they’re missing are the technical skills and access to tools.

It only took me 1.2 seconds to connect with the fellows and understand how their problem-solving abilities, their storytelling, and their way of connecting to people are going to be so influential in the tech space.

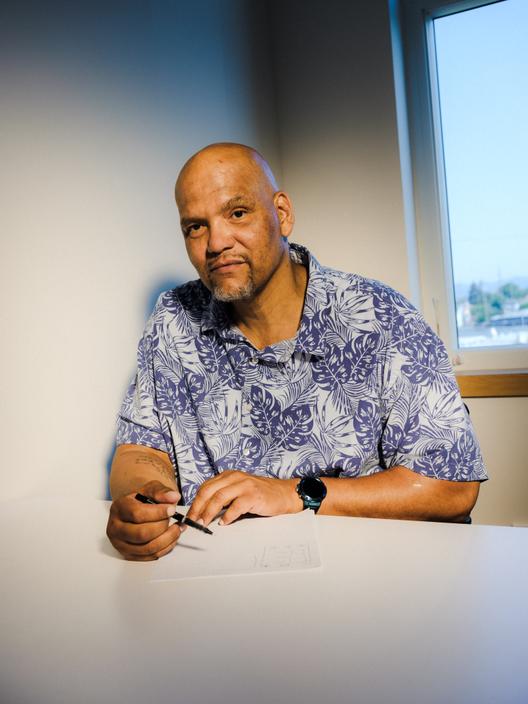

Ron, you served 27 years of your 48-year sentence, and during that time you developed an interest in tech. How did that influence your decision to apply for CROP?

In prison, I started going to self-help groups, and realized that I could live my life as opposed to life living me. Everything changed. I actually took over a clerk position from Jason, and one of my coworkers showed me how to code using Microsoft Access. I started writing little programs and fell in love with it. That led to math classes, then people asking me for help, and I became a tutor. It became my passion. I was a peer literacy mentor helping guys get their GED.

Right around the time I had the possibility of getting out, CROP opened up, and one of my friends sent me an application. I didn’t know what UX was. So I did a little research and was like, “Okay, this is totally connected to what I do.” It’s just one extension beyond. Through CROP, I’ve met people who are stone-cold, locked-down engineers, but they have a love for design. I’m getting goosebumps even talking about it.

I was actually the first person to come onto the residential campus in Oakland. I left prison, went to brunch, and got dropped right off at the gate and was immediately embraced by the founders. I cried. It was just so surreal.

Michele, you started doing advocacy work while in prison. How did that work lead you to CROP?

Michele has written an essay about a prison funeral for The Marshall Project and the experience of being in a women’s prison during the pandemic for Elle.

In 1991, I was sentenced to two consecutive life without the possibility of parole (LWOP) sentences. At some point, I thought, “I’m going to do something with my time rather than just do time.” Inside, LWOPs were excluded from self-help groups and educational programs, so my friend and I started a support group that evolved into us being proactive and writing letters [to legislators]. I put on events and formed garden committees, workshops, and walk-a-thons. In 2018, I was given a very rare governor’s commutation, and in 2021, I paroled from prison after serving 30 years.

After my release, my first two jobs were cleaning houses and warehouse work, and I could see that I was getting locked into this minimum-wage hamster wheel. I learned about CROP through another reentry program. CROP is giving me the opportunity to upskill. Thirty years ago, there weren’t a lot of pathways for women to go into tech. There were a lot of societal constraints, so I’m having this amazing experience of all these doors being open, coupled with the belief: “I can do this.” And as an LWOP advocate, my being out here is an opportunity to show society that we’re human beings and have the ability to transform.

Jason, can you walk us through the philosophy of the program? How is it structured to set fellows up for success?

People coming out of incarceration have experienced various levels of trauma, and they need to be in a space where they can unpack that limiting belief system and imagine something different for themselves. So the program is made up of four pillars. The first pillar is about learning an empowered mindset, developing digital literacy skills to navigate the world, and gaining financial understanding to manage their money.

The second pillar focuses on skills. There is an abundance of reentry programs that teach truck driving and construction, but we believe that people coming out of incarceration have more to offer than just their physical labor. There’s intellectual capital as well. The future of work is tech—that’s for sure. We identified what qualities would translate well to the tech space, and landed on business-to-business (B2B) sales and UX design.

The third and fourth pillars focus on employers and future housing. There’s a very heavy stigma about formerly incarcerated talent, so we knew we needed to do the work of promoting Fair Chance hiring practices. We need to keep people in a safe space where they are treated with dignity.

Ron, Michele, you’re now entering into the second pillar of the CROP program focused on skill development. What’s been your experience of transitioning into UX design?

When I opened up Figma, I was blown away. I see how it facilitates ease in getting your ideas out. I may not be able to put my thoughts into words, but I can draw it. You can kind of do anything in there; it’s just limited by you. I’m still on the learning curve, but by the time this program’s over, I’m going to be good at it.

Everybody here supports you, wants you to succeed, and will do anything to make that happen, like coming at two o’clock in the morning to help you do some paperwork. I’ve cried more times since I’ve been out—just out of happiness and being overwhelmed with the beauty of people—than I have in my entire life.

When I went into prison, tech was in its infancy. To go from 2005 Windows Excel to Figma, it’s like, “Now I’m in a Ferrari. I’m in a Lamborghini.” There’s an intentionality to it. I’m coming from basically an analog experience to what’s streamlined and industry standard and loving it. I liken the whole process to being on an amplified college track. Overall, I understand what a design sprint is, or what a user journey is. But some of the technical things that have given me a run for my money were as simple as changing a Google sheet into a PDF and emailing it out. That’s the value of having on-site instructors and coaches. And also, there’s this thing called YouTube [laughs]. So I’ve learned to G-T-S: Google That Shit.

A lot of the questions you’re asking in UX design—What is the problem? What other angles could you come at it from? What are the materials you’re going to use?—are exactly what I was thinking about inside. For example, you don’t have a lot of storage space in prison, and your room is very small. You want to store your pencils, but you don’t have cabinets or drawers. So what do you have? Vertical space, and some of it is metal. How do you attach something to metal? You can’t buy magnets. However, your headphones have tiny magnets in the ear cups. You can’t access Ziploc bags, but you can repurpose the small bags medications come in. So, I would take apart my headphones, attach the magnets to the side of the bag with tape, and stick the bag onto the metal lockers, along any area of the metal bunks, or onto the metal bars along the windows as a way to hang up my pencils.

This is the resourcefulness and resilience of people who are incarcerated. We have to problem-solve every day in the most extreme circumstances with hardly any resources and materials to work with in an attempt to make our daily lives better, and we’re able to succeed.

We have to problem-solve every day in the most extreme circumstances to make our daily lives better, and we’re able to succeed.

Alexis, how do you level the plane for a diverse array of experiences?

Within the UX design track, there’s a wide variety of skill, ability, and demographics. It ranges from coming in at zero to straight-up nerds who have fought for all different types of technology on the inside. Dexterity-wise, even the ability to use an iPhone or a laptop—things that seem so second nature to us—is not a given.

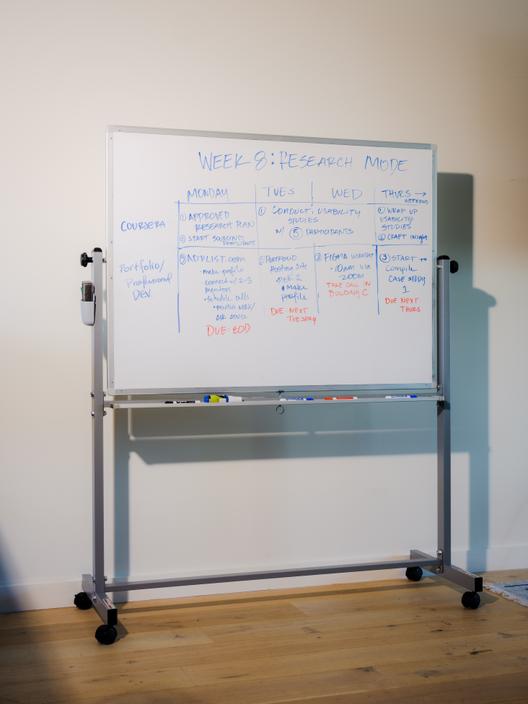

I’m using Coursera’s UX design certification as the foundation for the coursework while weaving in daily exercises in Figma through Figma for Education. I’m using Figma as the main workspace because it’s the industry standard, and there are so many helpful tutorials and ways to extend into the Figma Community.

What’s even more important than what we’re teaching is how we’re teaching—the behaviors we’re modeling, and how this space looks and feels. There should be spaces for collaborative work; there should be spaces for individual, heads-down work. We tried to model a version of the tech office. We have a daily standup. Instead of lectures, we call them meetings. I’m trying to stay away from classroom vernacular and use workplace vernacular. We cover how to communicate in meetings, how to send emails, how to facilitate with people in the industry. The nuances of the workplace are brand new.

Having exposure to industry norms, lingo, and culture seems like a huge aspect of the CROP program. This June, the fellows attended Config, Figma’s annual conference in San Francisco. What was that like?

It blew their minds. Their eyes were huge. They were very much like, “We didn’t understand anything about what they said, but oh my God, how exciting and cool what you can do with Figma.” So their curiosity grew, and now they’re trying to sprint when I need them to jog [laughs].

It’s kind of like when you take your kids to the lake and say, “Today, you’re going to learn how to swim,” and you throw them in. Because it was designer-centric, this was the exposure I needed to realize that tech is creative, and the people involved in it are really open and accepting. To see the cutting edge of apps that are coming out, it was just incredible. I think each one of us left exceptionally inspired and motivated.

That was the first conference I’ve ever been to. Nothing can prepare you for that. All of these people from every nationality, every size, every age, all into this thing that I’ve never even heard about—I saw their excitement and the importance of product design. How we’re interacting right now, all of that is going to get decided by somebody. I want to be a part of that. I want everybody to have a say in how that looks and works.

You mentioned the stigma associated with hiring formerly incarcerated individuals. How do you envision CROP being a part of changing that?

We’re here to provide you with a new perspective on your talent pipeline. These people don’t need a hand up; they need an opportunity because they have an uncommon level of resilience, determination, and appreciation. Nobody wants to be judged by their worst choice.

I just see opportunity. On the Fourth of July, we were on the roof, and we could see the Oakland skyline, and we were up there watching fireworks with popcorn. I just had an emotional moment where I screamed out at the top of my lungs like, “I can have that. I can have a piece of the city. I can own a house. I can have a career that I love and have a family.” I was like, “Wow! Everybody should feel this.”

Jenny Xie is the author of the novel Holding Pattern, a New York Times Editors’ Choice and National Book Award 5 Under 35 honoree. Her writing has also appeared in places like The Atlantic, Esquire, The Washington Post, Architectural Digest, and Dwell, where she was previously the Executive Editor.